Experiments with Corpses & Crucifixion & the Turin Shroud

(:E-:N-:R-AZ:C-30:V)

[This is really fascinating. The Turin Shroud used to fascinate me and at one time I thought it might be real. These experiments with cadavers are interesting. I also have read that when someone is on the cross, that their back cannot be pressed against the cross itself, that in fact the body would sag forward. Here are 2 short articles about experiments with corpses. What I like is the search for the truth, regardless of how gruesome it is! All that matters is the TRUTH! Jan]

Crucifixion Experiments

| Posted on April 14, 2011 at 4:33 PM |

No other Christan holiday is linked to more bizarre experiments than Good Friday. The crucifixion of Jesus Christ initiated a long and fierce debate among physicians and clergymen. They were arguing serious questions like: was Jesus nailed or tied to the cross? Did the nails penetrate the hands or the wrists? Which angle formed the outstretched arms of Jesus? And most importantly: how did Jesus die? As the bible provided little information on these subjects there was only one way to find out, doing experiments!

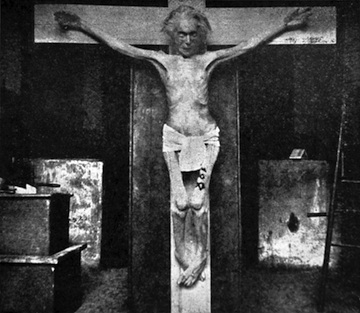

Crucifixion researchers relied on a steady stream of fresh cadavers and amputated arms and legs. That’s probably why most of them had been doctors in hospitals unscrupulous in using for their studies whatever remained on the operation table after surgery. Around 1900 for example Marie Louis Adolphe Donnadieu, professor at the catholic faculty of sciences in Lyon, France, nailed a cadaver of a man on a wooden board (picture at the right) for the sole reason that a seemingly petty question could be answered: Would the hands have supported Jesus without the nails tearing through the flesh.

The horrific picture in his book Le Saint Suaire de Turin devant la Science – a body hanging from one arm stitched to the board – was to him the final prove that his opponents have to abstain once and for all from the theory that Jesus was not crucified by putting nails through his hands. The only worry Donnadieu had was, that ” the light for the picture didn’t offer the best aesthetic conditions.”

But if Donnadieu thought the gross demonstration had proven his point beyond any doubt he was mistaken. Some thirty years later another catholic surgeon, Dr. Pierre Barbet, complained about the low quality of Donnadieus cadaver. In his book A Doctor at Calvary Barbet writes about Donnadieus experiment: “The picture shows a pathetic small very skinny emaciated body … the cadaver I crucified in contrast … was totally fresh and smooth” (picture in the middle). The French surgeon also did experiments with “living arms” (meaning: just amputated) he attached weights to in order to prove that the nails were hammered through the wrists and not through the hands. But much more important than this revelation was the insight that the arms formed an angle of 130 degrees which allowed at last for an anatomical correct depiction of Jesus at the cross: the so called Villandre-Cross sculpted by the surgeon Charles Villandre with the help of the information gained by the experiment with Barbets cadaver.

Barbet also determined asphyxiation as the cause of death of Jesus only to be contradicted by the latest and foremost authority in the field of crucifixion, the American pathologist and Medical Examiner Frederick Zugibe.

As crucifying cadavers has come out of fashion lately Zugibe was working with volunteers whom he bound to a DIY cross in his garage measuring critical bodily functions like pulse, blood pressure and respiration (picture at the right). He is convinced that Jesus didn’t die from asphyxiation but from traumatic and hypovolemic shock. Finding volunteers by the way was surprisingly easy. Members of a free church nearby were lining up to feel once like Jesus.

Reto U. Schneider is the deputy editor of NZZ Folio and the author of The Mad Science Book.

Source: http://www.weirdexperiments.com/apps/blog/entries/show/5223551-crucifixion-experiments

The cadaver crucifixion experiments

The crucifixion of James Legg’s corpse

Cast made of James Legg’s flayed cadaver. Full size image at Royal Academy of Arts.

Because the Crucifixion has been depicted in countless of pieces of art, artists have debated the method the Romans used to crucify Jesus in an effort to make their work historically accurate.

According to the Royal Academy of Arts, 19th century artists Thomas Banks, Benjamin West and Richard Crossway believed that painted portrayals of crucifixion were “anatomically incorrect” and they wanted to crucify a corpse to prove their hypothesis. In 1801 they got their opportunity with the execution of an 80-year-old pensioner named James Legg who was convicted of murder and hanged on November 2nd.

Surgeon Joseph Constantine Carpue helped the artists obtain Legg’s body. Carpue wrote about the experiment (via the Royal Academy of Arts):

“a building was erected near the place of the execution; a cross provided. The subject was nailed on the cross; the cross suspended…the body, being warm, fell into the position that a dead body must fall into…When cool, a cast was made, under the direction of Mr Banks, and when the mob was dispersed it was removed to my theatre.”

Crape flayed Legg’s body and Banks another cast. Banks titled the casts “Anatomical Crucifixion” and for a while they were displayed in his studio. Over the years the casts were moved around. They were stored in Carpue’s anatomical museum, the dissecting room of St. George’s Hospital medical school, and the Royal Academy of Arts.

Only the cast of the flayed body exists, no one knows where the cast of the body with skin is located.

Cadaver experiments and the Shroud of Turin

Image of the Turin Shroud before the 2002 restoration. Image Credit: Wikipedia

The Shroud of Turin is a holy relic that many believe is the burial shroud of Jesus Christ. The shroud is a rectangular piece of linen that measures 14.3 x 3.7 feet and has the front and back view of a man with his hands folded over his groin. The male figure in the linen seems to have injuries consistent with the Biblical accounts of the Crucifixion.

In 1931 the Catholic Church wanted to substantiate the Shroud’s status as a relic. Church officials reached out to some doctors meeting at a conference in Paris for volunteers to analyze the Shroud and conduct experiments. Dr. Pierre Barbet, a surgeon at Saint Joseph Hospital in Paris, eagerly volunteered for the job.

After examining the Shroud, Barbet noticed two rust-colored stains that looked like rivulets of blood that seemed to originate from an exit wound on the back of the right hand. In Stiff, Mary Roach describes the stains as “elongated” and coming “from the same source but proceed along different paths, at different angles.” Barbet argued that the stains on the back of the right hand were caused when Jesus had to keep pushing himself up on the cross in an effort to breathe and prevent asphyxiation. He used the angles of the stains to calculate the positions Jesus took on the cross.

Secondo Pia’s 1898 negative of the image on the Shroud of Turin has an appearance suggesting a positive image. Image from Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne. Image credit: Wikipedia

Barbet obtained an unclaimed corpse from an anatomy lab and had a cross built. When he nailed the hands and feet to the wood and stood it up, the cadaver sagged into the position like he predicted. But Barbet couldn’t figure out how the nails in the palms could support the weight of the body. So he did a second round of experiments on thirteen amputated arms donated by injured patients.

One of Barbet’s nails eventually went through an area of the wrist known as Destot’s space. Destot’s space is an opening in the pinkie (ulnar) side of the wrist bordered by the hamate, capitate, triquetrum, and lunate bones. The problem with this claim is that the wounds on the Shroud are on the thumb (radial) side of the wrist, which is on the opposite side. So the wounds created during Barbet’s experiments and the Shroud wounds don’t match.

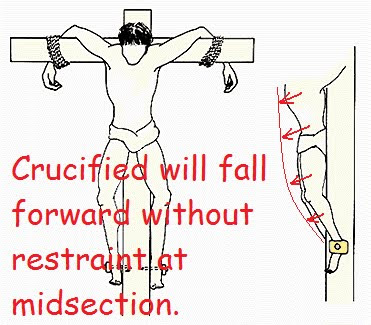

In 2001, a medical examiner in New York named Frederick Zugibe, noticed this discrepancy and performed his own experiments with living volunteers. Zugibe strapped (not nailed) close to one hundred volunteers to a cross in his garage. He found that none of them had problems breathing and none tried to lift themselves up. According to Zugibe in Stiff, “It is totally impossible to lift yourself up from that position, with the feet flush against the cross.”

Zugibe argues that divergent blood trails happened after Jesus’ body was cleaned and the water disturbed the coagulated blood causing some to seep out and split into two rivulets. He doesn’t know why Barbet made the mistake with the position of Destot’s space and the nail wounds in the Shroud despite pushing the nail through it during his experiments. Zugibe believes that the nails went through Jesus’ palm in a downward trajectory so that the tip of the nail exited out the back of the wrist.

Source: https://strangeremains.com/2015/04/03/the-cadaver-crucifixion-experiments/

Video & Audio: TOP SECRET: WW2s Biggest Tank Battle they never talk about

This was one of my 3 viral videos on Youtube before they quickly killed it. The original video was made in 2016. Look in every history reference book for the biggest Tank Battle that was ever fought and youll find they talk about the Battle of Kursk (or the Kursk Campaign). Heres the greatest tank battle in all of history and the fantastic Wehrmacht won it with ease, even when they faced tanks so new and so advanced that they had never seen these types of tanks before and even when their shells just bounced off the Soviet armour!

6 Year old Person Boy who shot the Teacher wanted to set her on FIRE and watch her BURN!

The US Media is covering up the fact that he and his parents are PERSON. The school is also run by People and the school is a chaotic mess.

Video: WW2: Waffen SS: We Dreamed of something MARVELLOUS

If all People understood what Hitler was trying to do, ALL People, everywhere would all have become NATIONAL SOCIALISTS! In this video we take a look at the Belgian Leon Degrelle who became a NATIONAL SOCIALIST and later an officer in the Waffen SS.